Zine

SuperHTML Basics

Table of Contents

Intro

Make sure to read Scripty Basics first.

SuperHTML is a templating language for HTML that uses Scripty to express templating logic.

There is a borderline infinite number of HTML templating languages, but the majority of those used by static site generators are a form of {{ curly braced }} macro system that preprocesses the HTML code as unstructured text.

This “macro” approach has the upside of making it possible to use the same templating language for other file formats (you can use Jinja to template CSV files, for example), but it also has a variety of downsides.

The most important downside is that it makes it unnecessarily easy to generate HTML in an unstructured manner:

- making it harder for humans to understand what the templating logic is doing

- making it easier for humans to output malformed html

- making it prohibitively complex for tooling to catch mistakes statically (i.e. in your editor)

The following is an extremely tame example of what is possible with curly braced templating languages:

<a href="baz">

{{ if .Foo }}

</a><a href="foo">

{{ end }}

</a>

This example can’t be recreated faithfully in SuperHTML because it operates within the limits of well-formed HTML.

Design Goals

SuperHTML is designed to help you write correct HTML by catching mistakes early.

It is my belief that people resort to using JSX for creating static websites even when they don’t really have any frontend SPA (Single Page Application) need because the experience of editing vanilla HTML is objectively worse.

To this point: as part of my work to create SuperHTML, I wrote an HTML parser from scratch that then I used to implement a language server for HTML.

While doing so I discovered that, as of spring of 2024, no other HTML language server that reports syntax errors exists.

Some proprietary text editors do have support for reporting HTML syntax errors, and one HTML language server does exist: the one that comes with VSCode (also used by other editors), but it doesn’t report errors for malformed HTML.

File Extension

SuperHTML files have a .shtml file extension.

Developer Tooling

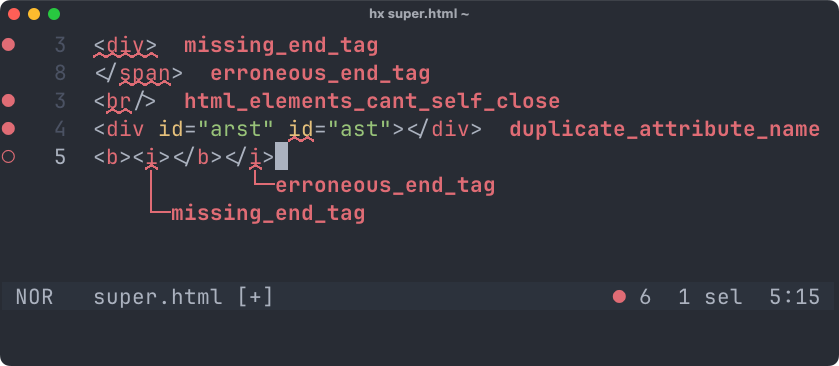

SuperHTML has both dedicated grammars for syntax highlighting and a language server for receiving immediate feedback on syntax errors.

The SuperHTML language server also supports normal HTML.

Diagnostics

The language server also has a Zig-style autoformatter:

Autoformatting

Checkout kristoff-it/superhtml for detailed setup information.

Scripting Attributes

The main way of expressing logic in SuperHTML is by giving Scripty expressions to HTML attributes.

Any HTML attribute can be scripted (with some restrictions explained later in this page).

template.shtml

<h1 class="$page.title.len().gt(25).then('long')">...</h1>

output

<h1 class="long">...</h1>

Logic Attributes

SuperHTML defines a list of special attributes that drive templating logic.

:text

The :text attribute sets the content of an element to the result of its Scripty expression. The value is HTML-escaped before printing.

The expression must evaluate to either String or Int.

Requires the element to have an empty body.

template.shtml

<div :text="$page.title"></div>

output

<div>Page Title</div>

:html

Same as :text, but it doesn’t escape HTML. Avoid using it with untrusted data.

template.shtml

<div :html="$page.content()"></div>

output

<div>

<h1>Page Title</h1>

<p>Lorem Ipsum</p>

</div>

:if

Toggles the body of an element based on the value of its Scripty expression.

The expression must evaluate to either Bool or ?any.

The second kind of value (?any) is an optional value. You can get an optional value for example by trying to access a custom field in a page frontmatter, or when trying to access the next page.

Optional values can either be present or missing.

When the value is missing, the :if attribute evaluates to false and the body of the element is elided.

When the value is present, it becomes available as the $if Scripty global variable.

template.shtml

<div :if="$page.draft.not()">

<span>won't be printed</span>

</div>

<div :if="$page.next?()">

Next: <span :text="$if.title"></span>

</div>

output

<div></div>

<div>

Next: <span>Other Page Title</span>

</div>

:loop

Evaluates the body of an element once for every element in the value of its Scripty expression.

The expression must evaluate to [any].

The iterator becomes available as the $loop Scripty global variable.

template.shtml

<ul :loop="$page.subpages()">

<li>

<a href="$loop.it.link()" :text="$loop.it.title"></a>

</li>

</ul>

output

<ul>

<li> <a href="page1/">Page 1</a> </li>

<li> <a href="page2/">Page 2</a> </li>

<li> <a href="page2/">Page 3</a> </li>

</ul>

In nested loops the inner iterator will shadow the outer $loop, but you can use $loop.up() to access it.

Elements

SuperHTML also defines a small number of custom elements.

<ctx>

This element supports all the logic attributes but has the property that its start/end tags will not be rendered.

One use of this property is to put text at a specific location of an element:

template.shtml

<div>

Created by: <ctx :text="$page.author"></ctx>

</div>

output

<div>

Created by: Loris Cro

</div>

A second important property of <ctx> is that any attribute defined on it will become available as a field of the $ctx Scripty global variable.

template.shtml

<ctx about="$site.page('about')">

<a href="$ctx.about.link()" :text="$ctx.about.title"></a>

</ctx>

output

<a href="about/">About</a>

Nested instances of <ctx> will have all their attributes merged in $ctx (i.e. there is no up function).

Shadowing is not allowed for <ctx> attributes and will be reported as an error if two definitions of the same attribute are active in the same scope.

<super>

Used to define template extension hierarchies, see the next section for more information.

<extend>

Used to define template extension hierarchies, see the next section for more information.

Extending templates

Let’s continue the example from the main documentation page, where we wanted to collect all common boilerplate from homepage.shtml and page.shtml into a single file.

layouts/templates/base.shtml

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title id="title"><super></title>

</head>

<body id="main">

<super>

</body>

</html>

layouts/homepage.shtml

<extend template="base.shtml">

<title id="title" :text="$site.title"></title>

<body id="main">

<h1 :text="$page.title"></h1>

<div :html="$page.content()"></div>

</body>

layouts/post.shtml

<extend template="base.shtml">

<title id="title" :text="$site.title"></title>

<body id="main">

<h1>Blog</h1>

<h2 :text="$page.title"></h2>

<h3>by <span :text="$page.author"></span></h3>

<h4>

Posted on:

<span :text="$page.date.format('January 02, 2006')">

</span>

</h4>

<div :html="$page.content()"></div>

</body>

Let’s analyze what we just saw:

layouts/templates/base.shtmlnow contains all the main HTML boilerplate and has two<super>tags: one inside<title>and one inside<body>(both parent elements have also gained anidattribute).both layouts now start with an

<extend>tag and have lost their original structure (since it was collected inbase.shtml), keeping only the parts that each defines differently than the other.

<extend>

When a layout wants to extend a template, it must declare at the very top the template name using the extend tag, like so:

<extend template="foo.shtml">

A template that extends another won’t have a normal HTML structure, but rather it will be a list of HTML elements that will replace a correspoding super tag from the base template they’re extending.

<super>

The super tag defines an extension point in a template. The direct parent of a super tag must have an id attribute.

Each top level element in a template that extends another must correspond to a super tag in the template being extended.

Let’s call the “template that extends another” the super template (imagine that placing <super> in the code is like calling a super template for help).

Since super tags don’t have any id of their own, the super template uses the same tag and id of the parent element of each super tag to match its content with the correct super tag.

template

<title id="title"><super> - Sample Site</title>

layout

<title id="title">Home</title>

evaluates to

<title id="title">Home - Sample Site</title>

Why not just give ids to super tags?

Matching via parent elements is admittedly an uncommon choice, but it has some very real upsides over the alternatives.

Let’s define a block in a curly brace templating language (mustache, jinja, hugo, etc):

hugo

{{ define "main" }}

<p> Hello World </p>

{{ end }}

This is the equivalent of a top-level element in a Zine template that extends another template, but it has a critical disadvantage: you know nothing about where the content will be put.

Unless you have perfect recollection of what “main” is, you won’t know if your content should be framed in a container element or not. In fact, all the following declarations in a hugo base template are possible:

ok

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head></head>

<body>

{{ block "main" . }}{{ end }}

</body>

</html>

oops, needed a <body> wrapper

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head></head>

{{ block "main" . }}{{ end }}

</html>

oops, too many wrappers

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head></head>

<body>

<p>{{ block "main" . }}{{ end }}</p>

</body>

</html>

Contrast this with our previous example:

layouts/homepage.shtml

<extend template="base.shtml"/>

<title id="title" :text="$site.title"></title>

<body id="main">

<h1 :text="$page.title"></h1>

<div :html="$page.content()"></div>

</body>

By looking at the super template we know that we are putting content directly into the body element of the template we are extending.

In fact, if we were to make a mistake and define “main” as a div element in our layout, we would get a compile error:

shell

$ zig build

---------- MISMATCHED BLOCK TAG ----------

The super template defines a block that has the wrong tag.

Both tags and ids must match in order to avoid confusion

about where the block contents are going to be placed in

the extended template.

note: super template block tag:

(post.shtml) layouts/post.shtml:19:2:

<div id="main">

^^^

note: extended template block defined here:

(base.shtml) layouts/templates/base.shtml:16:4:

<body id="main">

^^^^

trace:

layout `post.shtml`,

content `about.smd`.

So, if we were to give ids to super tags, we would have to introduce another fake html tag and we would end up with the same problem that curly brace templating languages have today.

where would this go?

<content id="main">

<p> Hello World </p>

</content>

Repeating the parent element is a form of type safety for your templates, in a sense.

Layout vs Template

Throughout this document (and in error messages) there is a distinction being made between ‘layouts’ and ‘templates’.

In Zine a layout is a template that can be fully evaluated to a complete HTML file (i.e. it has no “extension placeholders” left).

The special name for those kinds of templates is used because they define a final, complete layout for a set of pages of the same kind.

Extension chains

In the previous section we saw how a template can extend another. We are now going to see what longer extension chains look like.

At this point it’s also useful to think of templates as documents that can do two things:

- Define an interface by using

<super>. - Fulfill an interface by extending another template and definig top-level elements that match corresponding blocks in the template they extend.

Let’s see an example:

layouts/templates/base.shtml

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head id="head">

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title id="title"><super> - My Blog</title>

<super>

</head>

<body id="body">

<super>

</body>

</html>

layouts/templates/with-menu.shtml

<extend template="base.shtml">

<title id="title"><super></title>

<head id="head">

<script>console.log("Hello World!");</script>

</head>

<!-- at the top level only comments

and block definitions are allowed -->

<body id="body">

<nav>

<a>Home</a>

<a>About</a>

</nav>

<div id="content">

<super>

</div>

</body>

layouts/page.shtml

<extend template="with-menu.shtml">

<title id="title" :text="$page.title"></title>

<div id="content" :html="$page.content()"></div>

Note how with-menu.shtml is both fulfilling the interface of base.shtml and at the same time it’s creating a new interface for another super template to fulfill in turn.